“I would make them all learn English, and then I would let the clever ones learn Latin as an honour and Greek as a treat.”

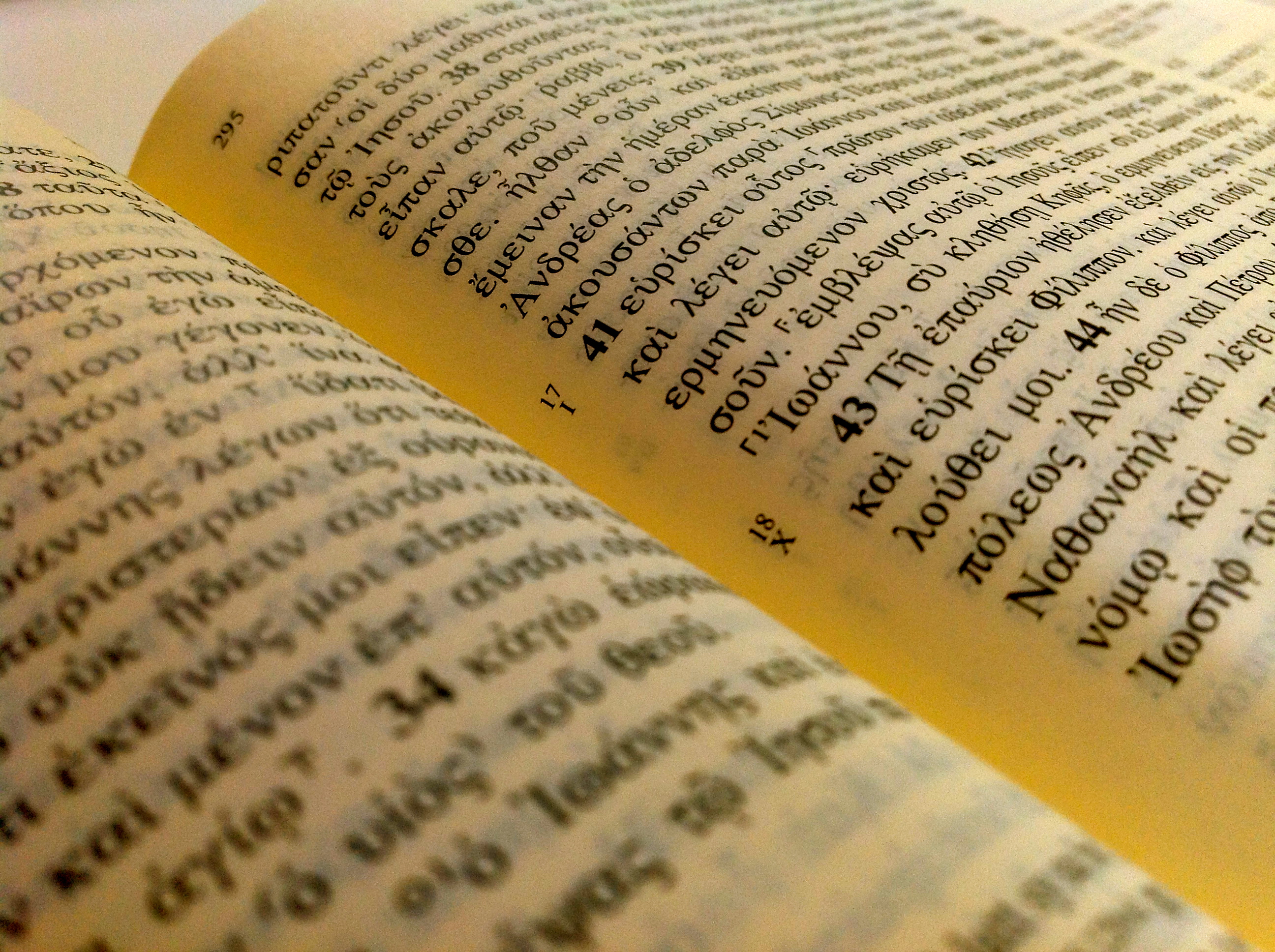

So said Winston Churchill, upholding the study of Greek as a crowning achievement of schoolboys. Many people first express an interest in learning the ancient Greek language because they wish to read the New Testament in its original language of composition, especially those who uphold the Bible as divine Scripture. It is evident to those who know more than one language how tricky it can be to translate words, concepts, and idioms from one language to another without losing some of the force or meaning of the original language. While biblical scholars over the centuries have done an excellent job of producing high-quality translations of the biblical text, it is, nevertheless, still a translation. Thus, many people, upon learning that the New Testament was originally written in Greek, have a desire to learn to read the Greek for themselves.

The problem is, the ancient Greek language developed over the span of centuries. Not only were there different dialects of Greek spoken in different parts of the Mediterranean world, but the Greek language itself continued to change over time. So what kind of Greek should a student learn if he or she wishes to read the New Testament?

While many agree that it is rewarding to read the New Testament in its original language of composition, some believe that students should begin by learning classical Greek first, that is, the Greek that was spoken and written during the height of ancient Greek civilization (especially in Athens in the 5th century BC). Others believe that one should simply learn biblical Greek, the Greek that was used during the time the New Testament was written.

As someone who has studied both, I would argue that one should learn classical Greek first even if one only wishes to read the New Testament. Learning classical Greek provides a broader understanding of the Greek language, makes it easier to read New Testament Greek, and benefits one’s study of the Greek New Testament overall.

Knowledge of classical Greek allows one to gain a broader understanding of the Greek language as a whole.

“Classical Greek” is a broad term which is usually used in contrast to “biblical Greek.” When one studies “classical Greek,” one is really studying the main dialects found in the literature of the ancient Greek civilization, especially of fifth-century Athens. Thus, those who study classical Greek are able to read the most important works of classical literature in the original language. This allows them to gain a deeper understanding of how the Greek language is used as a whole, along with the semantic range and function of individual words and concepts. Furthermore, the ability to read classical Greek literature, even just small exerpts, allows the student to become better aquainted with the ideas, thoughts, and expressions of Greek culture. Lastly, classical Greek is more structured and comprehensive in its morphology than later Greek, thus providing a better foundation in the language.

It is easier to read New Testament Greek after learning classical Greek first.

There are several reasons for this: first, Biblical Greek textbooks generally only present vocabulary from the New Testament, but students of classical Greek gain a larger vocabulary base because of the vast corpus of classical Greek literature. Not only do they learn most of the words in the New Testament, but they are also better equipped to handle literature outside of the New Testament, including the writings of the early church fathers; second, classical Greek grammar is more systematic and orderly, with more morphological forms and syntactical variation. This means that when students encounter a rare form of a word or rare syntax in the New Testament, they are better able to handle them because they may likely have encountered them in classical Greek; third, because of the more structured nature of classical Greek, students can more readily identify the unique styles of New Testament authors; and finally, classical Greek sentence structure is generally more complex, while New Testament Greek sentence structure is simpler and, thereby, easier to translate. Thus, when a classically-trained reader approaches the Greek New Testament, he or she will have the rewarding experience of reading the text with greater ease and understanding.

Knowledge of classical Greek provides valuable benefits for the study of the New Testament.

Biblical scholars and seminarians will agree that careful interpretation of a biblical text requires the ability to read other extant Greek literature in order to get a better understanding of the meaning of the text. In other words, one cannot thoroughly interpret the Greek text of the New Testament without referencing other Greek primary sources. Doing so allows you to explore the cultural milieu of the words, phrases, and ideas of the New Testament, an essential step in biblical interpretation.

But isn’t classical Greek more difficult?

Some may disagree and say that one should not learn classical Greek if one only wants to read the New Testament because of the higher degree of difficulty in learning classical Greek. The extra amount of material one would have to master and the complicated syntax of classical literature would make an already difficult language unnecessarily more difficult to learn, requiring a greater time commitment. Practically speaking, however, classical Greek is really not much more difficult than biblical Greek. Although it is true that one would have slightly more material to learn, the syntax of classical Greek is generally more consistent than biblical Greek. If one is already going to put in the effort to learn a challenging ancient language, one might as well do it thoroughly. Most people who start with classical Greek say that it is a breeze to read the New Testament afterwards.

Others argue that classical Greek is irrelevant for the study of the New Testament. They believe that time spent on acquiring classical vocabulary and grammar is better spent memorizing every word in the New Testament. They also believe that they will forget all the “extra” material they learned if they don’t regularly encounter it in the New Testament. This is not necessarily true. The time spent on acquiring classical Greek vocabulary develops one’s awareness of the usage of Greek language as a whole. Greater exposure to Greek literature develops one’s awareness of the kinds of contexts in which individual words are used, aiding one’s understanding of the language. Moreover, many of the most common words in classical literature also appear in the New Testament. There is considerable overlap. The additional vocabulary will enhance your reading of the New Testament by allowing you to, for example, compare why a New Testament author would use one word over another that does not appear in the New Testament. Although it is certainly possible to forget classical Greek if one only reads the New Testament, the diligent Greek student would not restrict himself to the New Testament alone. Serious readers who wish to get the most out of the Greek text will want to continue referencing other Greek literature, including classical texts, to enhance their understanding of the New Testament.

So, should one learn classical Greek if one only wants to read the New Testament?

Absolutely. A little extra effort at the beginning will eventually provide you with a broader understanding of the language, make it easier to read New Testament Greek, and enhance your study of the text of the New Testament.

If you are considering taking up Greek as a beginner, you will have to decide which road to choose. Learning Greek requires a commitment of time and effort. It is important to choose from the beginning that which will serve you better in the long run.